“One for all, all for one.” – Alexandre Dumas

With nearly four billion people in some kind of lockdown, we now live in a completely different social environment than four months ago. And our daily choices – staying home, wearing masks, limiting our shopping, etc. – all affect the spread of the novel coronavirus. Our behaviour will determine that of the virus.

How has the way we act changed and what can motivate us to alter it further? INSEAD Professor Lucia Del Carpio described how social norms are adjusting during the pandemic in a recent webinar in the Navigating the Turbulence of COVID-19 series.

Clear messaging

Behavioural science can help in this uncharted territory, especially when it comes to getting the message out. “We are undergoing a massive global public health campaign,” Del Carpio explained, “a campaign to slow the spread of the virus. And the recommendations are, in a sense, simple, but difficult to comply, especially for particular groups. Hand washing, wearing masks in public, reducing face touching, and especially social distancing.”

“Any individual behaviour that limits contagion is contributing to slowing the spread of the virus. And we need to make people internalise this externality.”

With these rapid behavioural changes, effective public health messages without ambiguity are necessary. “We need to convey the urgency of fulfilling these new behaviours. But, we also need to sustain pro-social motivations at a large scale, which is very important. We need to stop thinking only about ourselves and think about us, collectively,” she explained. Governments have an important role. Combining recommendations with messaging about the risk associated with COVID-19 can have great impact.

She spoke about the need for persuasion: “If we want to implement these massive lockdowns, there's a huge amount of population that has to stay home. It's impossible that the government on its own can enforce these. We need to actually persuade people to want to go through certain behaviours.” Aligning the individual and collective interest is necessary to avoid the misinformation that leads to risky behaviours, like coronavirus parties. Linking civic duty to behaviours works. To encourage mask-wearing in public spaces, France’s Académie nationale de médecine has evoked the Three Musketeers’ motto for unity, for example.

It seems that the persuasion is working. Del Carpio parsed Google tracking information to uncover the global decline in going out. In the chart below, we see how in countries with severe lockdowns (dark blue), the compliance rate is serious, e.g. 80 percent of Indians staying home. For partial lockdowns or recommendations only, there is still a lot of compliance with the new norms. “People are reducing their mobility.”

Non-inclusive norms

There are, however, exceptions to compliance to the new norms. That’s because of the uncertainty around the coronavirus – how many people are really infected, what role asymptomatic people have in transmission – which “creates a sense of invisibility about the spread of the pandemic,” Del Carpio explained. This makes adoption of new norms difficult for some.

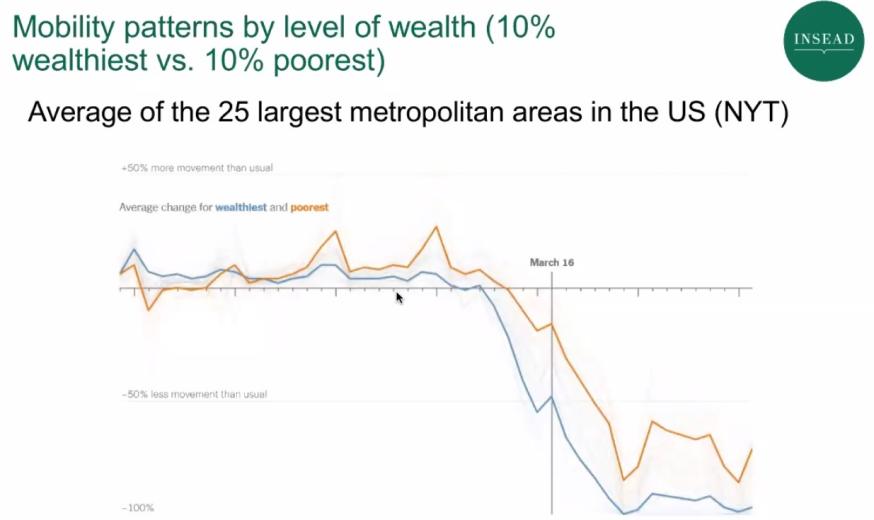

Some communities have a lower take-up rate for washing hands because their access to water is limited. Other vulnerable groups find social distancing – staying a metre or two away from others outside your household – physically nearly impossible. This is true not only in the developing world, but also for the working class in Europe and the US. The following graph shows how mobility for wealthy Americans was much less after lockdowns than those who had to continue to go out for work.

For “these lockdown measures in general,” Del Carpio said, “it's much harder to comply for certain groups.” For them, “we should emphasise the benefits to the recipient about taking care, but also the focus on protecting others, aligning with moral values.” We may also need other measures to help them comply (transfers to the poorest segments, etc.).

In the current health crisis, many people feel threatened and fearful. Del Carpio warned that these emotions “can vary our perceptions of risk, and that can lead us to discrimination or feelings of prejudice against others. And we need to address these.”

Social context matters, but culture is also an important factor. For some, it’s not a question of available space, but social norms about how physically close we should be to one another.

Pro-social compliance

One of the hardest hit countries in Europe is Italy, where people conversing in very close proximity is a norm. Del Carpio spoke about a recent article that measured civic capital with data from Italy.

“Civic capital is good for acting collectively, for contributing to the public good. In situations like this, it could actually make you also change completely your behaviour and be able to comply with social distancing better than others.”

“In societies where there is very high civic capital, people like to interact with each other. We see this in the mobility patterns. Probably they meet often. They are good neighbours. They interact. And then, what we see as the recommendations come in, the news about the epidemic come in, these regions of high social capital start changing their behaviour very fast,” Del Carpio explained. Thinking collectively, societies with civic capital can make difficult behaviours – like not visiting elderly relatives – more manageable and inspire faster compliance.

The article assessed civic capital, which relates to social norms, through three different measures: blood donations, a survey on trust of others, and newspaper readership.

More community spirit

Del Carpio emphasised that most citizens in locked down nations are complying with the recommendations or orders (depending on the severity of the lockdown). There are, however, noisy protestors who reject the new social norms.

Regarding protestors in the US and other countries, she said, “Clearly people are weary about not being able to earn an income…these are difficult cases to handle. Overall what helps is giving more information, but at the same time at this particular point, I think enforcement could also be relevant. I think we need to also counteract all of those movements with all of the positive experiences that have arisen…I think we still have the tools and the ability to drive these [people] towards cooperation and towards the right measures that we all want to comply with.”

Future norms

Moving forward, how will norms change? Once lockdowns are over and we are all outside together, we need to accept that information about where the epidemic is travelling is necessary for the public good. Collecting these data is now largely managed by mobile apps in South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore – countries which managed to flatten the curve for the initial outbreak. Countries all over the world are considering options for apps that use GPS and/or Bluetooth to garner information about which mobile devices have been in proximity to one another. Major companies like Apple and Google are also working on them. Contact-tracing apps have clear benefits in terms of precision information about contagion rates.

For these apps to work well, they need massive (around 60 percent) take-up rates. That said, apparently just 30 to 40 percent will reduce the spread of contagion. Of course, this raises certain worries about individual rights. Del Carpio pondered: “Can we give away a little bit of our privacy in order to be able to save lives? I think this is a very important question.”

She is an advisor for the launch of a government contact-tracing app in Peru. “Contact tracing is both a community protection device and an instrument for public policy,” Del Carpio said.

The trade-off of digital tracing “allows us to map the epidemic. It gives a lot of interesting information for public policy, for health policy, and for citizens to adapt their behaviour. But it's not for free. It's at a cost of giving some personal information.”

Like for other communication about norms, governments need to consider the tone to use when messaging someone who has recently been near a person who has tested positive. Will they receive a scary message saying “You may be infected!” or something a little more supportive?

New behaviours will be expected from citizens receiving a warning. They will need to receive encouragement. With the support of the health system, it will become possible to generate compliance and ask certain actions of people, for example, self-isolation. “And of course for this to happen, it requires a lot of trust and civic capital or social capital, in order to be willing to share your private information for higher good,” Del Carpio explained.

“Behavioural economists, in general, believe in the interplay among many motivations that are impacting human behaviour. There are intrinsic motivations (like altruism). There are extrinsic motivations (or incentives). There are also reputational motivations,” she said. "And what is good about this is that in a sense, multiple behavioural norms can emerge as equilibrium and it depends on us. If everybody is complying with this behavioural social distancing, then the defector is going to have some stigma. We can create good norms to help us deal with this pandemic.”

INSEAD’s webinar series “Navigating the Turbulence of COVID-19” feature expert inputs on key issues surrounding pandemic control and current countermeasures around the world. Sign up here.

No comments yet.