In many organisations, especially complex or global firms, saying “no” is structurally safer than saying “yes”. If you approve a risky initiative and it fails, you might be blamed. But if you delay, defer or block it? There’s no immediate downside and you don’t carry the cost of inaction. Someone else – typically the business itself – is left holding the empty bag of missed opportunity.

One of the most subversive truths in modern organisations is this: It costs nothing to say “no”. No capital, no commitment and no courage required. In fact, it is the safest word in the corporate dictionary. The gatekeeper who says “no” is seldom questioned. The blocker is rarely blamed. After all, nothing happened. And that’s precisely the point.

This isn’t malice. It’s design.

Here’s the rub: The opportunity not taken is never counted.

“No” by design

We live in a system where entire departments – indeed, entire careers – are built around the art of prevention: preventing risk, preventing deviation and preventing embarrassment. It is a curious game. The fewer initiatives that proceed, the fewer there are to fail. And the fewer that fail, the safer we all feel.

This means that in most organisations, authority and accountability are misaligned. Central functions – legal, compliance, HR, finance and IT – often hold the power to approve or deny, but they are not accountable for the outcome if things don’t move forward. They operate at a distance. And that distance creates a kind of corporate vacuum. But here’s the rub: The opportunity not taken is never counted.

No one audits the innovations that died in infancy. No metrics track the momentum lost in meetings, or the ambition bled out through caution. And so “no” remains unscathed – reputation intact, inbox cleared and conscience clean.

The vacuum of veto

Let us look at the anatomy of this phenomenon. In many organisations, particularly those with large central functions, authority is dislocated from consequence.

These different functions, be it legal or finance, can exercise a veto without owning the outcome. They can delay a project, rewrite a proposal or reshape an idea without the lost opportunities ever showing up at the moment of truth. These functions do not conspire against progress. They operate, albeit in good faith, within a vacuum. Their job is not to imagine what could be, but to protect what already exists.

The problem is not one of competence – it is one of misalignment. It is, in many ways, a classic case of the inverse principle: The very structures put in place to prevent failure end up institutionalising it. In the name of prudence, we create paralysis. In protecting against risk, we forfeit initiative. And in optimising for safety, we design out the possibility of greatness.

In short, we have built systems where power is disconnected from responsibility, and where responsibility is rarely accompanied by power.

When corporate functions operate in a vacuum

When an organisation’s functions operate in a vacuum, they act as if their job is to minimise the downside, not to enable the upside. The business unit may want to launch a new product, forge a new collaboration or enter a new market. But instead of partnership, they get process, which could take the form of “We’ll need a few more rounds of review”, “This doesn’t fit our global template” or “It’s too risky given our current posture”.

The underlying assumption is this: It’s better to be the department that blocked a mistake than the one that enabled a success. That mindset is rational within the function. But organisationally, it’s fatal. While no single “no” feels dramatic, the cumulative effect is corrosive: a culture of disengagement, a slowing down of ambition or a quiet exodus of entrepreneurial energy.

The hidden asymmetry at the heart of the firm

We need to ask deeper questions: Who decides? And who delivers?

In the best of worlds, these are the same people. But often, they are not. Typically, we have the approvers who exercise discretion without exposure, and the doers who carry exposure without discretion. This is not just inefficient. It is demoralising. It breeds compliance, not creativity. Caution, not courage.

Let’s name the core issue: Authority without accountability is a veto without vision. And accountability without authority – being asked to deliver without the mandate to decide – is just as problematic.

A simple framework: from mirror to design prompt

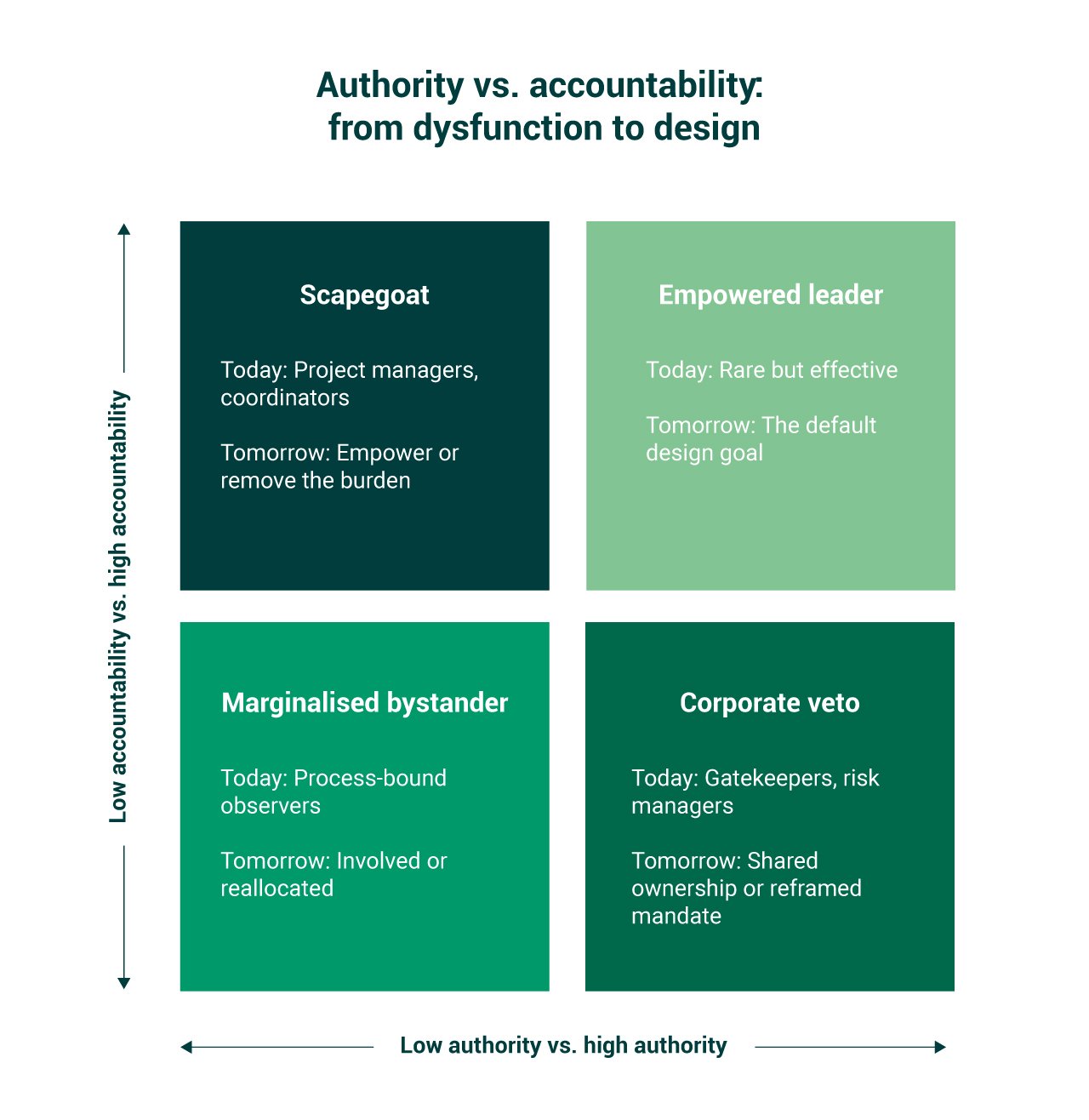

To make this visible, here’s a simple device to map authority against accountability.

- In the top right: The empowered leader says “yes” and lives with it. This is where autonomy meets ownership. It’s rare, and it’s gold.

- In the bottom right: The corporate veto, to whom “no” is easy and responsibility is scarce, represents risk aversion dressed as good governance.

- In the bottom left: The marginalised bystander who observes, records and complies, but never contributes. They have no voice, no liability and no use.

- In the top left: The scapegoat, held accountable without authority, is the fall guy for strategic indecision.

This matrix is not a model; it is a mirror. A provocation. A prompt. It’s a way of asking: Where do we want more decisions to be made? Who is asked to deliver without being empowered to decide? And what would it take to shift more roles into the top right, where courage and consequence are aligned?

If we want to culivate more leaders who say “yes” and mean it, then our job is to design organisations where saying “yes” is both possible and worthwhile. In the end, the future belongs not to those who blocked the last potential mistake, but to those who dared to make the next beginning.

Edited by:

Geraldine Ee-

View Comments

-

Leave a Comment

No comments yet.