Not every CEO can be the next Steve Jobs, constantly conjuring up game-changing new ideas and revolutionary products. But what all CEOs and senior leaders can be is champions for innovation within their own organisations. They are the ones who can help give their employees the freedom and space to get creative, while also setting the boundaries within which this innovation can take place.

The former CEO of Finnish lifestyle brand Fiskars, Kari Kauniskangas, described his approach to the challenge of embedding innovation into his organisation this way: “It’s important for me to make sure our people have the desire, will and freedom to find better ways of doing business. In search of new ideas, we have to give them permission to go crazy! But we also have to create boxes that define their focus and challenge people to innovate in the areas of greatest need.”

Transformation through innovation

The impact of such leadership can be extremely powerful, helping a company to open up new product lines, move into new markets or even redefine its overall purpose or mission. Take the case of Ecocem, a small cement manufacturer that was looking to compete in a tradition-minded industry dominated by a handful of big companies. Founder and managing director Donal O’Riain realised that if Ecocem wanted to stand out from the competition, it needed to leverage the power of innovation to help address an unmet customer need.

For O’Riain, that need was a way to reduce the high environmental impact of cement. The production of cement is very energy-intensive and accounts for around 8 percent of total global greenhouse gas emissions annually. Yet there had been little or no effort within the industry to find a more sustainable solution.

Despite concerns from Ecocem’s board, O’Riain dedicated significant financial resources to research and development of potential solutions. He gave the company a clear direction by redefining its motto as ‘Innovation Driving Sustainability.’ He also created a special technology subcommittee, which saw members of his board liaise with managers working on key innovation projects. Not only did this give initially-sceptical board members an insight into the potential benefits of the innovations, it also helped offer further inspiration to Ecocem’s innovators by showing them that they had the support from some of the most important people in the organisation.

As a result, the Ecocem team were able to take advantage of an underused technological innovation – Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBS) – to develop a cement substitute which was just as strong as traditional cement products but had a much smaller carbon footprint.

While it took a significant investment of time, negotiation, research and resources to persuade regulators and clients of the true potential of switching to GGBS, the company was able to reshape their whole business model around this innovation. From being just another cement company, Ecocem is now firmly positioned as an environmentally conscious organisation whose range of innovative products are helping customers meet their key sustainability targets.

Reframing: a key process of innovating

Ecocem is a classic example of a CEO helping to reframe a company’s purpose. Reframing is a key mechanism for an organisation to adjust (and in some cases dramatically change) its current objective to react to shifting external and internal realities and help better prepare it for the future. For Ecocem, that meant changing their mission and embracing a new innovative product to meet the demands of a more sustainable future.

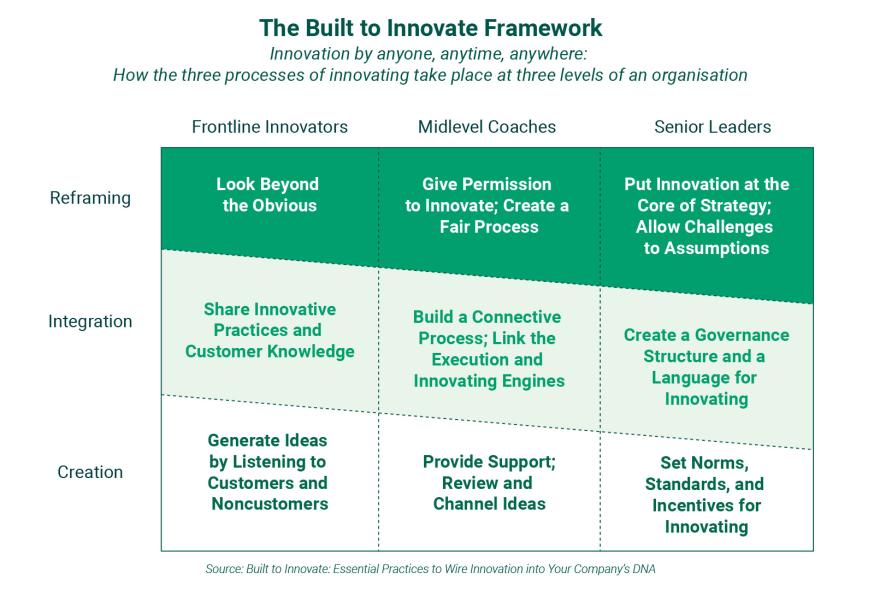

In my book, Built to Innovate, I identify reframing, along with creation and integration, as one of the three key processes needed to embed what I term an innovating engine into any organisation’s DNA.

As I’ve explained in previous articles in this series, creation is about giving employees the tools and motivation to generate ideas, while integration is about connecting these ideas, innovators, and resources across an organisation and linking them to the execution engine. Reframing is the practice of challenging assumptions that may hinder such innovation by encouraging team members to change their mindsets and reimagine their ways of working (as displayed in the graphic below).

In other words, it’s the CEO and their senior leader’s duty to take on the role of chief reframing officer, helping to broaden or redirect the company’s collective purpose and open up new spaces and avenues for everyone to look for new ideas inside the new larger ‘mental box’.

From commodity supplier to innovating partner

Kordsa, a Turkish manufacturer of tyre fabric, is another good example of a company that successfully reframed its mission through the impetus of its senior leaders. Under the direction of then-CEO Cenk Alper, Kordsa transformed its purpose from simple commodity supplier to ‘the Reinforcer.’ By working in partnership with customers and noncustomers, Kordsa started to develop innovative reinforcement solutions beyond the tyre industry, opening up whole new markets in the construction, electronics and aerospace sectors.

As with the case of Ecocem, this transformation was driven by the CEO taking the lead when it came to demonstrating a commitment to innovation, through training and investment, across the organisation. Alper, who is now the CEO of Sabancı Holding, of which Kordsa is a group company, has since reframed Kordsa’s mission again: to become a company that looks to ‘Reinforce Life’ by combining high-value-added reinforcement technologies with innovation in order to create sustainable value for all its stakeholders and society.

Reframing is everyone’s responsibility

Even though leaders of an organisation have a key role to play in the reframing process by creating the permission and space to innovate, it would be wrong to think it is solely their responsibility. As is the case with implementing the creation and integration processes driving the innovating engine, reframing can only be effective only if everyone, from frontline workers, middle management to senior leaders, is fully activated and contributing.

Frontline workers’ daily interaction with customers (and noncustomers) doesn’t just make them vital as a source of creative new ideas; it also means they are the best placed to provide concrete feedback on the validity of the current assumptions and beliefs around an organisation’s ways of doing business. Indeed, the popular Japanese concept of gemba is based on the idea that spending time at ‘the real place’ where your business value is created, be that a client meeting or the factory floor, is an excellent source of new ideas and new perspectives.

Of course, frontline workers need to feel confident enough to challenge their bosses and the team and bring any new ideas and innovations to light. This is where middle managers come into the reframing process. They are the ones who are responsible for creating fair process and embedding a climate of trust and psychological safety in the workings of the innovating engine so that the frontline workers feel they have permission to innovate. They help the frontline team feel confident in creating the ideas and then ensure that the good ideas are given the opportunity to be acted upon and implemented.

What the examples of Ecocem and Kordsa show is that the actions of senior leaders can be the catalyst for this innovating process to get started. By challenging current assumptions and the status quo, promoting transparency and demonstrating a willingness to experiment in their deeds and actions, a leader can help turn an organisation, even in a tradition-minded industry, into a powerhouse of innovation.

This article is part of a series using specific case studies from the book Built to Innovate to highlight the three processes – creation, integration and reframing – that will allow a firm to develop an innovation engine.

Anonymous User

21/02/2022, 10.02 pm

Thank you Ben, great read.