The beginning is a fragile point for many endeavours. We might consider that an ordinary event like going to the doctor will be the moment that utterly alters our course. But the initial steps in many processes inform the rest of the journey.

In the medical arena, early decisions can be the difference between life and death. We have seen this on a global scale with the Covid-19 pandemic. Countries that responded faster to the outbreak by focusing on testing and tracing have been more effective in controlling the virus’ spread.

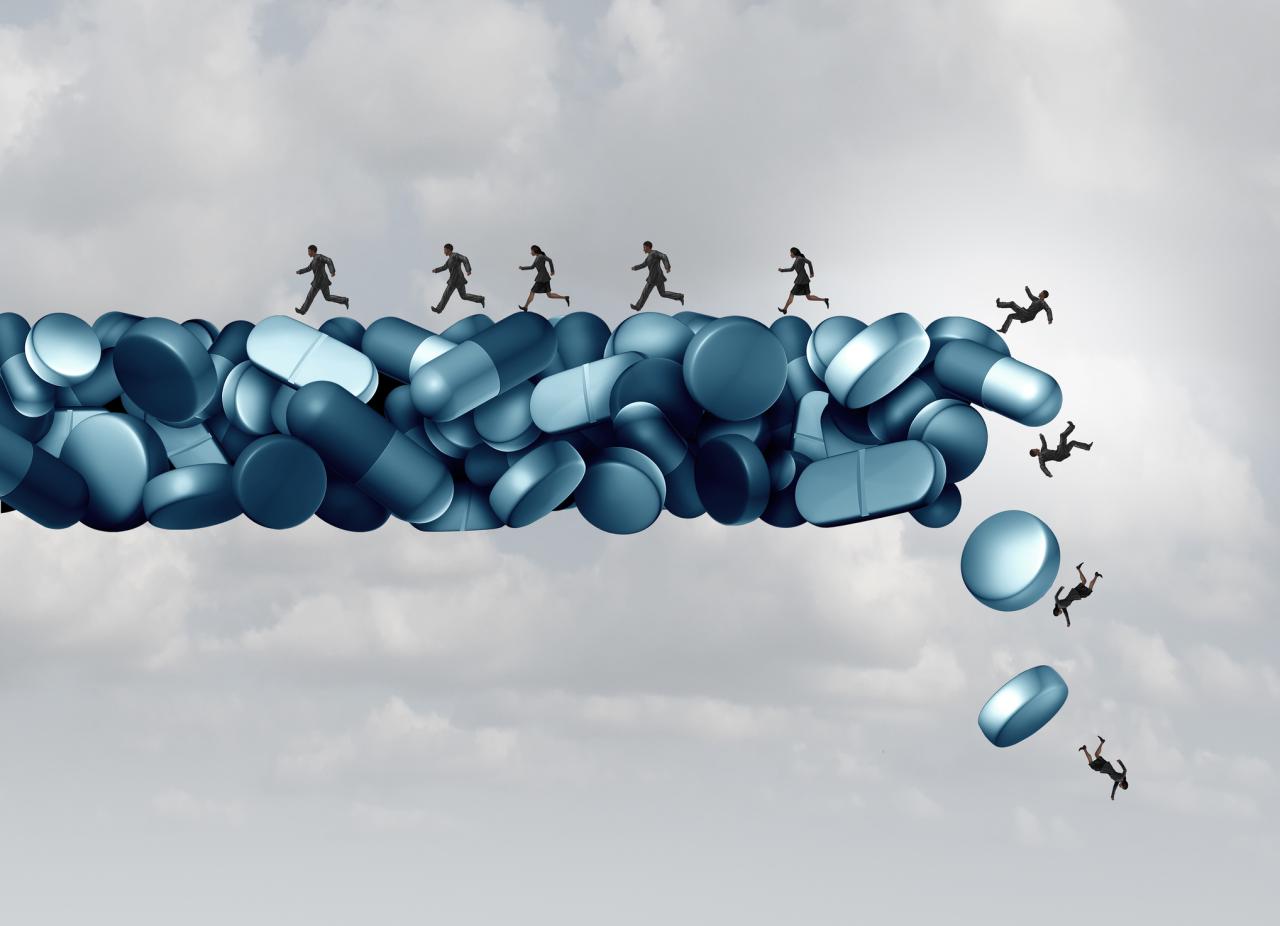

Sadly, coronavirus is not the sole public health crisis in the United States. Indeed, there has been a persistent and decades-long opioid epidemic ravaging the nation, affecting all socio-economic levels. In just a single year, 2017, 47,600 people died from opioid overdose. Tragically, the isolation induced by the Covid-19 pandemic only increased opioid deaths in 2020.

Opioid addiction in the US may start with a single prescription for pain relief. Modern pain medicines like OxyContin relieve pain, but some users also found that crushing the pills before ingesting them gave a potent high. The market for these drugs is phenomenal, with the US consuming more than 80 percent of the global opioid medication supply.

To tackle the opioid crisis, significant attention has been paid to treating those who are already addicted, such as weaning addicts off opioids or increasing the availability of naloxone to prevent fatal overdoses. But instead of tackling challenges after they've materialized, further down the road, could something be done earlier in the process to disrupt the pathway to addiction?

While patients might expect their treatment plan and clinical outcomes to be affected by their personal needs and preferences, some of my previous research has shown that the patient’s medical journey and final outcomes can also be affected by organisational factors. This includes the doctor they see, how busy the hospital is when they arrive, and who else is in the hospital at the same time as them.

Although this may be alarming, especially for the patient arriving in a heavily congested emergency room, it also points to the potential for improving patient outcomes through better management of the care delivery process. With this in mind, I sought to investigate whether simple managerial changes could help tackle the opioid crisis at its root.

A management solution

In our forthcoming article in Management Science, “Curbing the Opioid Epidemic at its Root: The Effect of Provider Discordance after Opioid Initiation”, my co-authors* and I studied a group of patients receiving their first opioid prescription in the primary care setting. We asked a straightforward question: When patients return for a follow-up appointment, should they see the same doctor who wrote the initial prescription, or should they see someone new?

It turns out that this seemingly simple question has significant ramifications. Using historical data, we found that visiting a different doctor for the follow-up appointment reduces – by nearly one third – the likelihood of long-term opioid use a year after the initial opioid prescription.

Based on this finding, one managerial intervention would be to have a flag in the patient record, so that if a patient calls up again for an appointment within a certain period after an initial opioid prescription, they are assigned to a second doctor for the follow-up appointment. While such an intervention may only be possible at a multi-provider medical practice, a very quick calculation suggests that more than 15,000 conversions from new to long-term opioid users could be prevented each year.

We also observed that long-term opioid use was 20 percent lower amongst patients who saw their regular primary-care doctor (or personal doctor) for either the initial or follow-up appointment. This points to a best-case scenario for patients concerned about the addictive properties of opioids: They should schedule the first appointment with their regular provider, but should a follow-up be necessary, it should be with a different doctor.

More medical data needed

Although rigorous testing demonstrated the validity of our findings, we caution against the rapid adoption of interventions until further evidence exists. From the medical community's perspective, we hope that our work will stimulate further robust clinical research. Because the effect size of more than 30 percent is large and clinically significant, we would like to see follow-up studies to verify these results in different settings with perhaps different methods and approaches.

These findings do, however, highlight the potential for improving patient outcomes by tweaking scheduling practices in the primary care office. Yet, we have no medical advice for physicians, nor would we say that opioids should not be prescribed. In fact, because of the observational nature of our study, the reasons for the change in outcomes remain a matter of speculation. It could be that patients who present in front of a second doctor are more willing to accept different answers, because their pain persists even after their initial prescription. It might even be the case that the second physician doesn’t prescribe opioids when the patient actually needs it. The issue of why opioid long-term use is reduced when a patient sees more than one doctor early in their care is a question for the medical community.

Whatever the reason, this early intervention does appear to have a significant effect downstream on long-term opioid use. What happens at the start of the patient journey in this case can alter people’s lives. When the initial doctor prescribes opioids, they should be aware that this first, seemingly innocuous decision sets the patient in a certain direction. Steering them onto a different path later might be difficult. Initial decisions impact long-term patient outcomes.

The big picture

Beginnings are crucial in other non-medical fields, of course. The outcomes are not necessarily life-or-death, but managers should consider the importance of first steps when planning for the long-term. Preparing the right model at the right time can make pivoting to other products or services easier, based on demand.

Doctors are the medical experts, and our paper clearly has no clinical advice. There are, however, operational changes that practice managers may consider when scheduling an individual’s first two pain-related appointments. We hope to start a conversation around what can be done earlier in the patient journey to prevent adverse outcomes. Early decisions matter.

* Katherine Bobroske (University of Cambridge), Lawrence Huan (University of Cambridge), Anita Cattrell (Evolent Health) and Stefan Scholtes (University of Cambridge)

-

View Comments

-

Leave a Comment

No comments yet.