The Great Recession may be far behind us, but for some, the scars remain. Financial institutions were not the only ones who were hit hard during this period. In a large-scale study, we show that the profound and acute economic stress of the crisis affected the mental health of children – sometimes with lasting effects.

Our research takes on heightened urgency given the broader mental health crisis facing children and adolescents. According to the OECD, between 10 and 20 percent of children worldwide suffer from mental health challenges, particularly conditions such as anxiety and depression. Moreover, studies have shown that children and adolescents who experience a mental health disorder can suffer persistent effects in education and employment outcomes. Given the socio-economic implications, understanding the external triggers of mental health conditions among children is vital.

Escalating risks

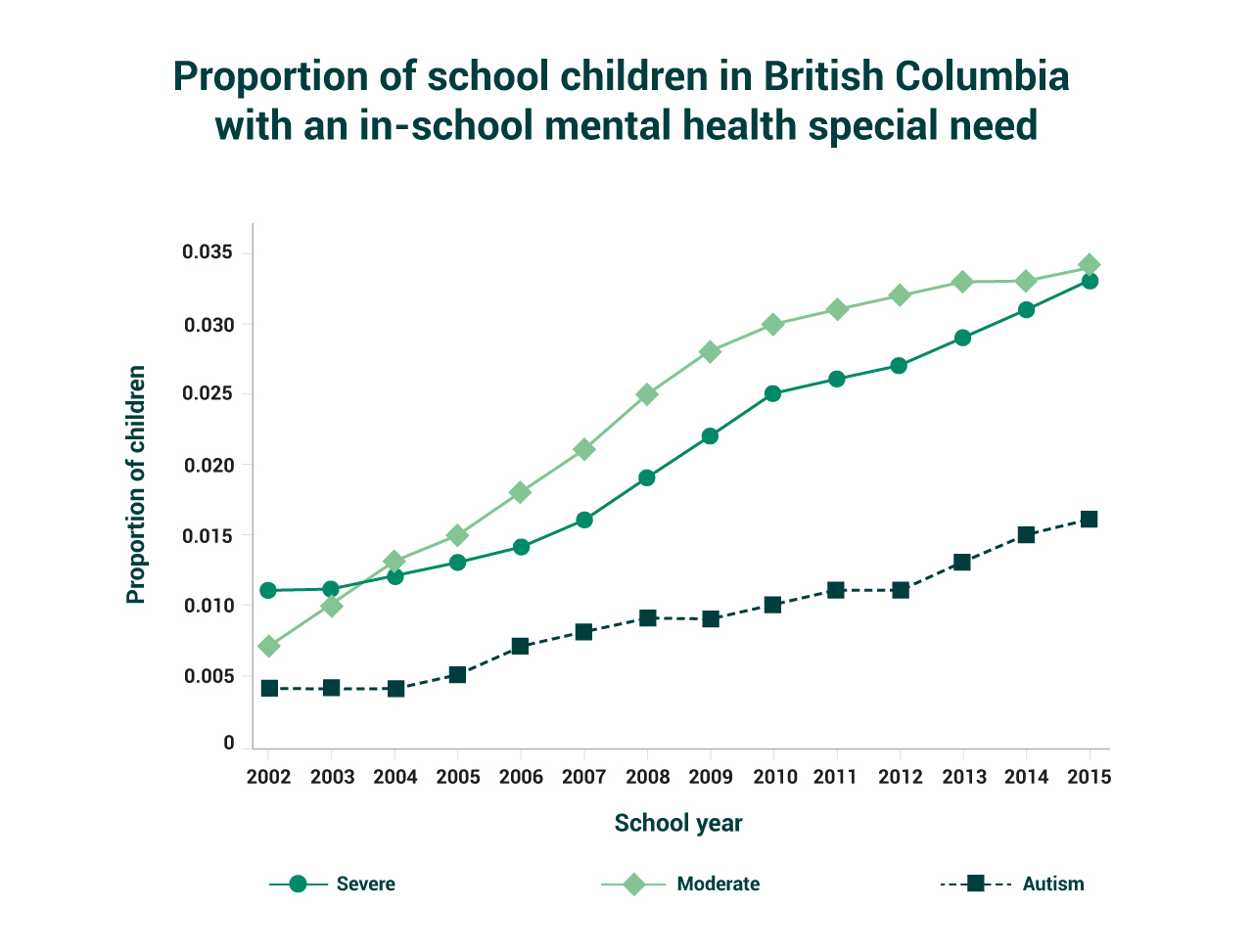

Our study shines a spotlight on the role of income in shaping children’s mental health outcomes, both through the financial resources it provides and through its broader effects on family stress and social relationships. Overall, in-school mental health designations increased substantially in British Columbia during the period of our study.

Source: British Columbia Ministry of Education public school administrative data

As shown in Figure 1, the proportion of children ever having received a diagnosis for a moderate (e.g. aggression, hyperactivity, anxiety or depression) or severe (extremely antisocial or disruptive behaviour in most environments) mental health condition increased from 2 percent to nearly 7 percent in 2015. Figure 1 also reveals a distinct increase in the rates of these designations starting in the 2007-2008 school year – the beginning of the Great Recession – and continuing through the 2010-2011 school year.

Unprecedented scale and accuracy

In our empirical study, we used administrative data covering the entire population of over 250,000 children in public schools in British Columbia, Canada to examine one factor that may have contributed to the trend of increasing mental health diagnoses depicted in Figure 1: a sudden change in earnings of these children’s families. Covering the period of 2002 to 2015, our study is built around the Great Recession (2007-2009) – when the unemployment rate increased 35 percent between 2008 and 2009 in Canada – which we leverage as an unanticipated negative shock to household earnings.

Our access to a large, administrative dataset gives us an important advantage over studies that use data obtained through self-reported surveys, which tends to result in small sample sizes and inaccuracies due to bias or misreporting. By linking each child’s in-school mental health designation to their parents’ tax files, our study provides highly accurate estimates of how fluctuations in household earnings impact children’s mental health diagnoses.

The uninterrupted data covering 14 years allows us to follow each child’s mental health trajectory both before and after the recession-induced reduction in household income. Our analysis involved examining the difference in rates of in-school mental health designations among children whose families experienced an earnings loss in 2008/2009 vs. children whose families did not experience a loss. We found that, by 2013, new mental health diagnoses among children who experienced household earning declines were 20 percent higher as compared to children whose household earnings were unaffected. By 2015, they were 28 percent more likely to receive new designations vs. children who did not experience the income shock.

Sadly, the effect of experiencing a recessionary earnings loss is persistent and grows, especially in children who experienced the loss when they were aged 10 or younger. We found that children who experienced a household income shock exhibited increased rates of mental health diagnoses as they entered high school in 2011 at ages 12-14, partly because their family earnings had not fully recovered by the end of our sample period. We also found that children in households that suffered substantial earnings loss experienced a significant increase in in-school mental health diagnoses.

Social safety net matters

Fortunately, Canada’s publicly funded universal healthcare system ensured that the children had some access to healthcare. Moreover, since Canada’s child-based cash transfer is based on income and not on parents’ employment status, households continue to receive financial support even if a parent(s) is out of work, which likely helped smooth any recession-induced income shocks.

As such, while the effects of a reduction in household earnings like those in British Columbia could apply to other parts of the world, the magnitude of the effect on children’s mental health might vary due to differences in social systems and social safety nets.

Take the United States, where healthcare coverage is less complete and healthcare benefits are largely tied to employment. The effect of the Great Recession on child mental health would likely be larger than that in Canada. Moreover, since tax and income transfer programmes (like the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit) are contingent on parents being employed, there would have been little backstop if parents lost their jobs or suffered pay cuts during the recession.

Smoothing shocks, shaping trajectories

Importantly, our evidence suggests that earnings shocks can have a strong and lasting effect on children’s mental health, complementing emerging literature examining the impact of financial stress experienced by children on their decision-making ability in adulthood. This has important policy implications.

To change the trajectory of at-risk children, policies must be aimed at mitigating the effects of income shocks on vulnerable families and offering support to students in school.

Canada has a relatively strong social safety net to support families with children, including programmes like the Canadian Child Benefit, universal childcare and federal employment insurance. Even so, protection against immediate income losses varies due to conditions of eligibility, and some individuals may simply not be aware of the various forms of aid available to them. In fact, it is not uncommon for benefits to go unclaimed because people are not aware of them.

Moreover, some families may fall through the cracks as access to such benefits may be contingent on conditions such as employment duration, rendering them ineligible for benefits such as employment insurance. An income transfer system that provides unconditional income support could help families smooth their income when they experience negative income shocks in the short run, and in turn, better protect children’s mental health.

In the long run, a large body of literature points to the effectiveness of government training programmes that help workers upskill to find new forms of work. Greater investment in these types of programmes may also potentially help mitigate the broader persistent decline in child mental health.

Edited by:

Geraldine EeAbout the research

-

View Comments

-

Leave a Comment

No comments yet.