It is almost impossible to buy food these days that does not purport to be healthy in one way or another. Everyone wants to make healthier eating choices, and food companies often try to present food as healthier than it really is, as I have outlined in previous Knowledge articles based on my research.

However, there is no agreement among experts, and certainly not consumers, about what “healthy” even means. For example, Kellogg’s sued the UK government over new regulations limiting the in-store promotion of foods that are high in fat, salt and sugar. The company argued that the formula used to measure nutritional value did not consider the nutritional elements added when its breakfast cereals are consumed with milk. It lost.

As the number of products that claim to be healthy increases, so does consumer distrust that they really are. A recent European study found that only 43 percent of consumers think that food products are generally healthy, and just 46 percent trust food producers. The growing disagreement over what it means for food to be healthy suggests that marketers’ claims do not match consumers’ expectations.

In order to investigate this further, Romain Cadario and I examined the ways food companies have labelled food products as healthy over the past decade and contrasted this behaviour with the preferences and associations of consumers.

Our research, published in the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, focuses on breakfast cereals in France and the United States. We chose this product category as it is popular and dominated by the same companies in both countries. Cereal packaging also makes numerous health claims despite the product having a mediocre nutritional quality.

Four ways to be healthy

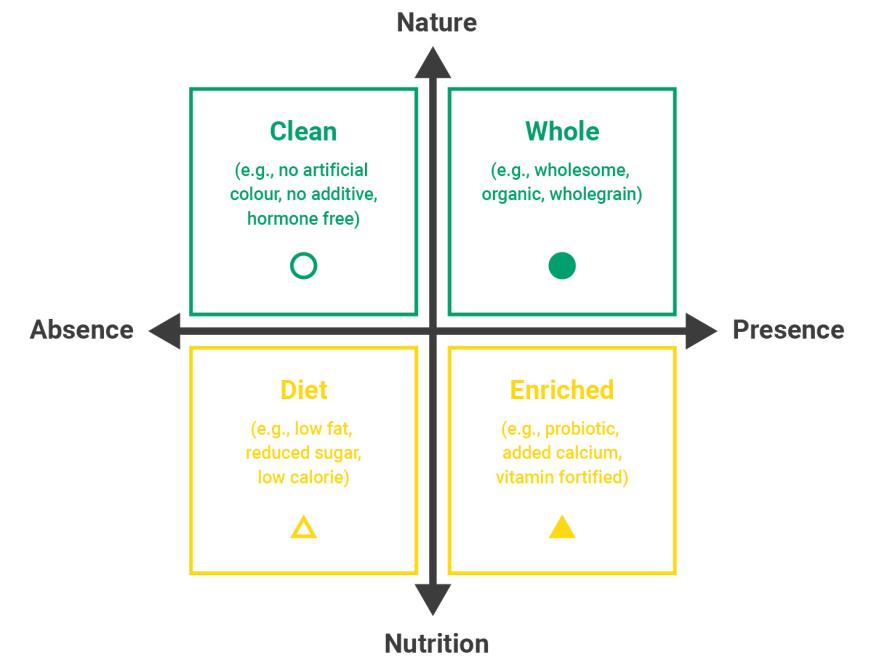

Our research builds on my previous study that found four distinct ways foods claim to be healthy.

Some brands claim to be healthy because they have improved the nutritional properties of the food. They use labels like “enriched” if they have added “good” vitamins and minerals or “diet” if they have removed “bad” sugar and fat. These are the traditional, nutrition-based ways to be healthy.

Other food products claim to be healthy “by nature”. These brands claim they have preserved the food's natural characteristics by either not adding anything bad (these includes claims such as “clean” or “free from” additives or hormones) or by not removing anything good (these includes claims such as “whole” or “organic”).

Increase in ‘clean’ labels

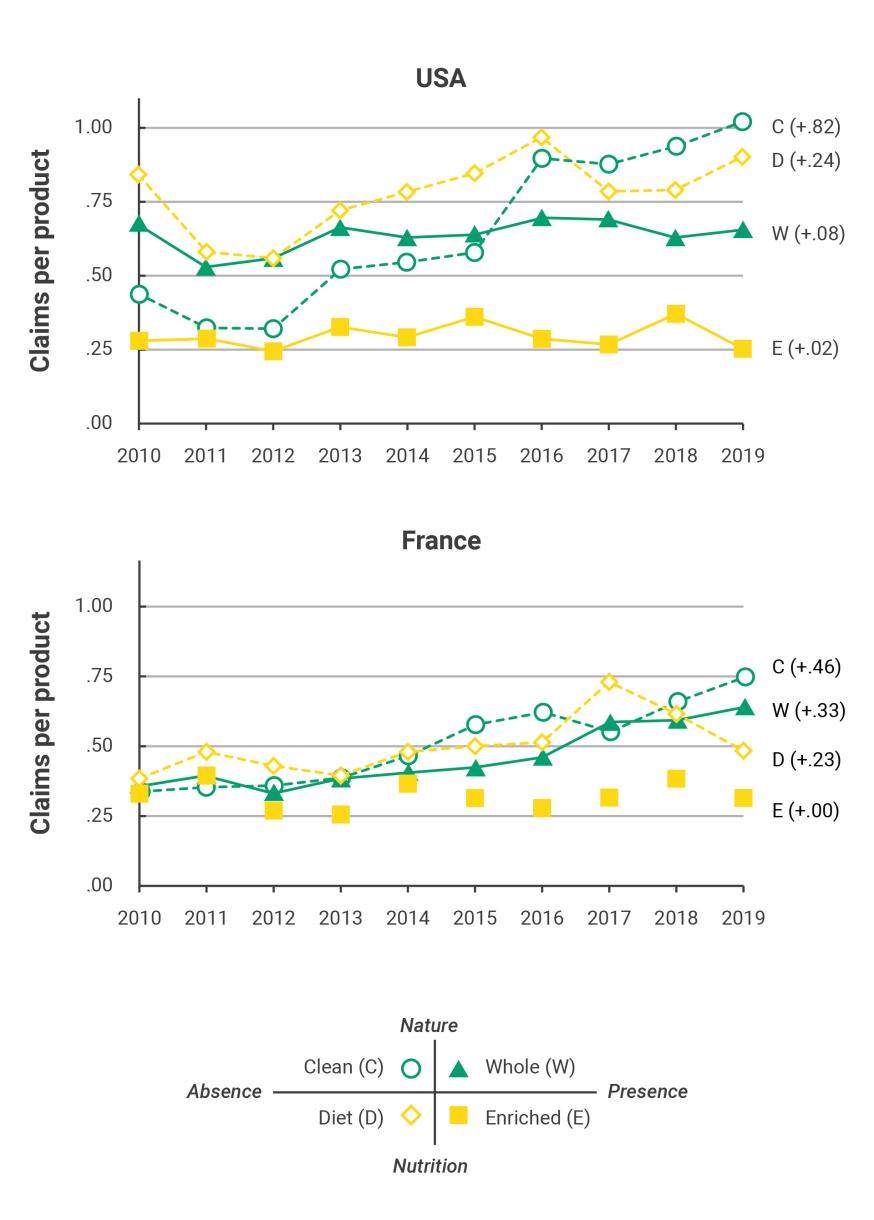

Using data on food-claim frequency collected by Mintel Corporation, we found that “clean” claims – labels that stress nothing artificial has been added – are the fastest-growing category in both France and the US.

“Enriched” claims are the least used, while “diet” claims grew similarly in both countries. “Whole” claims like “wholesome” or “organic” grew faster in France and are now the second most popular category, whereas they remained in third place in the US.

The following charts plot the number of claims that the product is “clean” (C), “whole” (W), “diet” (D), or “enriched” (E) for the average product in three categories (breakfast cereals, bakery products, and baby foods). The values in parentheses capture the change in the number of claims per average product over the ten-year period. In the US, for example, consumers could expect to see 0.82 more claims about “clean” over this period.

French match, US mismatch

We then took a closer look at how this contrasts with consumer preferences in each country. While prior research has focused on company behaviour or consumer response, it is rare to have both in the same study.

We collected and evaluated data on consumer preferences for these four types of claims from two samples of French and American consumers matched on age, gender, income and education levels.

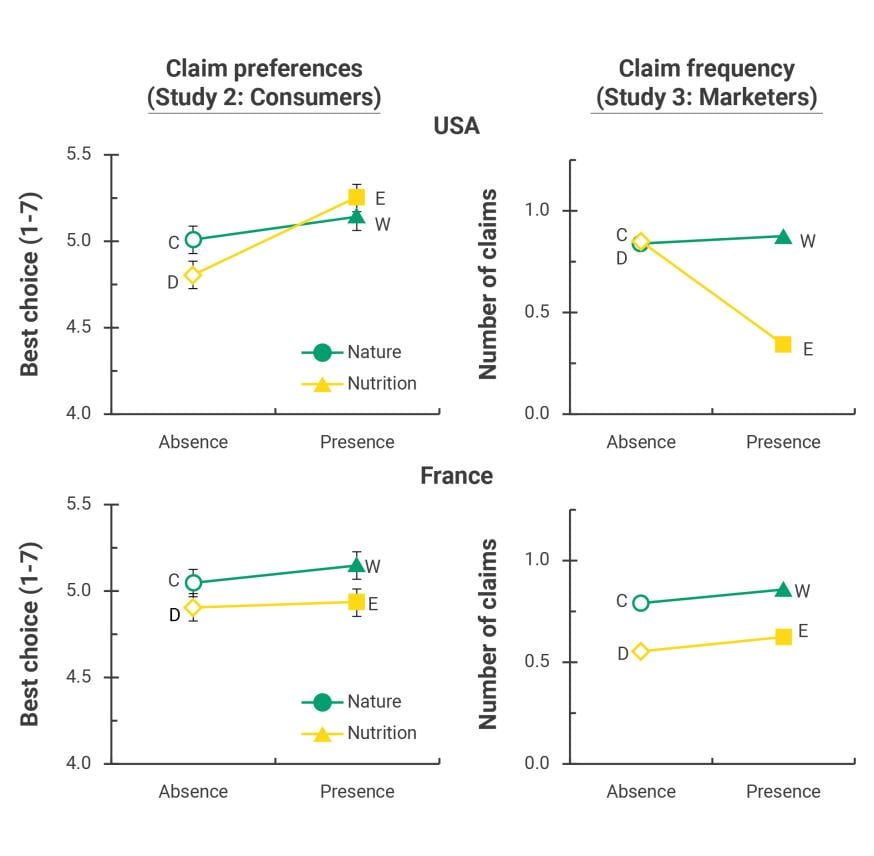

Our findings indicate that Americans prefer claims about the presence of good than about the absence of bad, as illustrated in the top left chart.

French consumers, however, prefer nature-based claims that the product is healthy because its natural properties have been preserved. This finding is presented in the bottom left chart where we see the green line (indicating preferences for nature-based claims) is above the yellow line (nutrition-based claims).

These marked consumer preferences should make it easy for marketers to give people what they want. We found this was the case in France where claims that consumers like most are also more frequently used on cereal packaging. As a result, the bottom right chart, showing claim frequency, closely matches the bottom left chart.

However, things are completely different in the US, where there is a big mismatch between the claims that people like and the claims that companies are using. The least-popular claims, those about “diet”, are very frequently used, while the preferred claims about products being “enriched” are much less frequent.

Why the US got it wrong

To understand why there is this mismatch, we pooled data on company ownership. Our findings suggest that public companies make fewer health claims on their packaging than private companies in both countries and yet have the highest matching rates. This suggests that companies can successfully match consumer expectations without making many health claims if they are the correct ones.

While big cereal manufacturers like Kellogg’s and General Mills market their products in the way American consumers prefer, we found that smaller, privately-owned companies are more likely to use “diet” claims that people like less. In contrast, French privately-owned companies make the same kind of claims that public companies make.

We explored several hypotheses as to why private companies are not marketing their products to meet consumers' expectations. The one that we think is plausible is that these smaller American companies are driven by a mission to improve the health of consumers, instead of just making health claims that consumers like. These companies are in fact doing what is healthier, which is to remove salt, sugar and other additives.

We came to this conclusion by analysing the names of the privately-owned companies. We observed a higher proportion of those that have company names referencing nutrition or health, such as “Low Karb”. This could explain why these companies don’t give people what they want – they are focused on giving people what they should eat, which is more nutritious food.

It is interesting to see that not all companies are consumer-oriented in the way we assume them to be. They do not necessarily focus on what the market wants. This could be because they are following a niche strategy where they only go after small subsegments of people who really want to lose weight.

Alternatively, it could be because they want to be the “good guys” and are going above and beyond what consumers want. What we are seeing in the US data suggests that some smaller companies understand they have a responsibility to offer more nutritious products.

Redefining ‘healthy’ and other abstract terms

It is difficult for companies when consumers are attracted to buzzwords like “natural”, “fresh” or “organic”, as these claims are not scientifically regulated and have no association with the nutritional quality of the food. Food marketers need to understand how consumers are interpreting healthy food, and keep track of how these opinions change, even when they do not align with nutrition.

These conceptual, catch-all words extend beyond the food industry. Nearly every company wants their product to be “cool” or “high quality”. However, these words can be interpreted in many different ways. It is therefore important to unpack what people mean when they use these casual terms. Often, we think we understand each other, but we are talking about vastly different things.

Edited by:

Katy ScottAbout the research

-

View Comments

-

Leave a Comment

No comments yet.