The “bigger is better” mindset has spread beyond the business world to the world of social impact. And for good reason: After all, isn’t it better to serve more people, and to seek efficiency through scale?

The problem is that disproportionate attention is being given to scale as the main indicator of the impact achieved. Open a typical impact report, and you will see the “number of farmers reached” or the “number of women empowered” being proudly reported. This would not be a bad thing if the reports also included a caveat that scale does not capture the whole story. But that message is rarely conveyed.

When it comes to measuring one’s contribution, quality of what is being achieved matters too, not just scale. Breadth of impact is of course worth considering, but so is depth, i.e. how much difference one really is making for each person one serves.

Taking depth seriously

Evaluating depth involves seeking clarity on who is being served, how underserved are they, and how valuable is your contribution to their lives. Consider the case of a venture that was set up as a chain of bakery cafés in Southeast Asia to provide dignified employment to severely disadvantaged people, like women rescued from trafficking. As the pressure to scale mounted, the enterprise’s focus shifted from “severely disadvantaged” to just “disadvantaged” (e.g. low-income people in general). This enabled scale-up, but came at the expense of depth.

Why do impact ventures often get tempted to prioritise scale over depth? Sometimes it is a business decision, as size is often correlated with financial sustainability. But often the decision is made as scale is just more visible, while measuring depth is hard. Pressure from donors and investors exacerbates the issue.

Depth is especially critical for most social enterprises. These ventures are meant to push the frontier of market-based approaches in extreme contexts, taking on issues that other businesses would view as unprofitable or too risky. Social enterprises recognise that trade-offs are often inevitable, and fight the pressure to adopt those “win-win” solutions that promise quick growth or profits, but might compromise on depth of impact. Instead, they often choose to have slower, more careful growth paths. They do seek to make enough money to ensure financial sustainability and reduce dependence on grants, but do not pursue profits and growth at the cost of their mission.

Case study: humanitarian entrepreneurship

Recently, I moderated a webinar as part of INSEAD’s SDG Week, featuring Aline Sara, an alumna of INSEAD Social Entrepreneurship Programme. Sara is co-founder and CEO of the social enterprise NaTakallam (“we speak” in Arabic), the subject of my new case study (co-written by Devanshee Shukla).

NaTakallam might seem like just another online language learning platform, like italki and Duolingo. Its website promises “award-winning, high-quality language learning programmes… for all levels of Arabic, French, Persian and Spanish”. But what sets NaTakallam apart is its mission: Its language sessions provide dignified employment to refugees and internally displaced people trying to rebuild their lives.

Sara acquired first-hand knowledge of the refugee crisis as a journalist covering the Arab Spring uprisings. Contrary to stereotypes of refugees being helpless individuals living on handouts in camps, many of them are motivated and well-educated individuals eager to earn their living and contribute to society. But they often cannot work due to legal barriers (like work permits) or social exclusion.

Sara realised that she could bring some of these people into the booming global language services market (expected to reach US$56 billion by 2021), connecting them to learners through a technology-enabled gig-economy platform. The impact would in fact go beyond the instructors receiving gainful employment (at an hourly wage equalling or exceeding the minimum wage in their host country) to bridges being built across cultures as the platform users made new friends and overcame stereotypes.

“We’re not a catalogue of languages,” Sara said during the webinar. “You provide background on your language skills and your interest, and we match you with the right partner.” She added, “We try to distribute the work as much as possible. If we were just a marketplace, the same five-star tutors would keep getting the students… But that would also limit the amount of impact... I would say people who come to NaTakallam are very much driven by the social impact, and the fact that they are getting to meet individuals like Ghaith and support individuals who might not have another lifeline.”

NaTakallam employee Ghaith Hallak, a Syrian refugee residing in Italy, shared what NaTakallam has meant to him: “I started in October 2015… I can say that was a turning point to me… In the morning, I have a student in Pakistan. In the evening, I have a student in California. And in the afternoon, I teach students in London. It helps me improve my skills and understand the outside world at the same time.”

In addition to one-on-one language sessions, NaTakallam offers translation services and educational partnerships with schools and universities. In its five-year history, it has paired nearly 180 refugees with 9,000 users, disbursing more than US$900,000 in wages.

If viewed from the perspective of mainstream entrepreneurship, this scale might not seem too large. Sara explained, “We run NaTakallam with an impact-first mindset, which means we are not thinking with the typical start-up mindset, which is rapid growth and returns… We want to grow, but we don't want to risk losing our impact to get those fast, rapid monetary returns.” Aline is very focused on her depth of impact, but this has come at a cost – NaTakallam has grown slower than it otherwise might have. Fortunately for NaTakallam, demand for online learning has seen a big boost during Covid-19.

Sara compares her reliance on gradual growth through internal funding to an entrepreneur “who comes home, opens his or her fridge, sees what’s already in the fridge and decides: This is what I'm going to build with what’s already in the fridge”. She worries that prematurely bringing in external funding can become a distraction. “It is like a marriage when you have an investor… If we meet an investor that is fully aligned, of course we will be open to it because the ultimate goal is growing our impact.”

It is not unusual for social enterprises to grow slowly as they take their time in perfecting their model. But they do not necessarily stay small forever. Consider BRAC, founded by Sir Fazle Hasan Abed as a small rehabilitation project following a conflict that displaced millions at the time of Bangladesh’s birth in 1971. Focused on integrated poverty alleviation programmes deeply embedded in communities, BRAC has nevertheless grown to be one of the world’s largest and most respected social sector organisations.

Three dimensions of impact

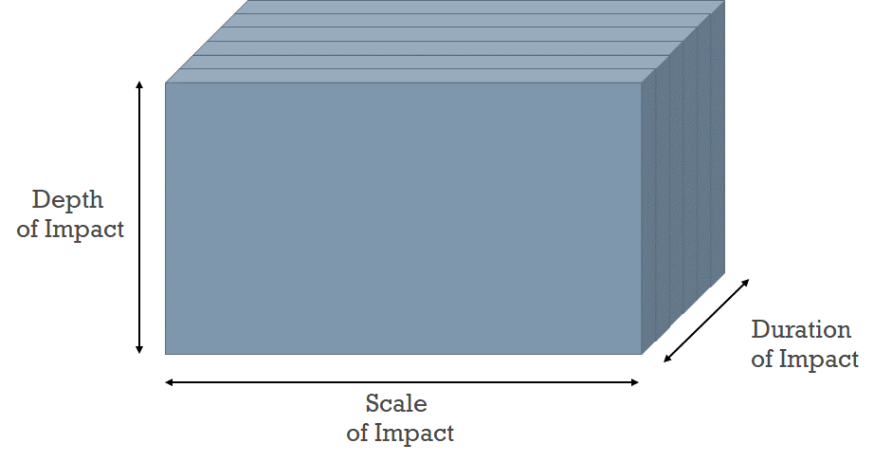

There is more to impact than just scale. The Silicon Valley-style “go big or go home” philosophy is far too black-and-white to do justice to the multi-faceted nature of impact. It is more useful to think of impact as the volume of a cuboid, whose three dimensions are scale, depth, and duration.

Kiva, started as a crowdfunding platform for microfinance, used to consider scale its metric of success. But then it realised that microloans achieve deeper impact in selective contexts, such as those where the loans come with low interest rates and flexible terms, and serve the most excluded segments – like refugees, immigrants or smallholder farmers. This realisation had led Kiva to carry out an overhaul of its strategy in order to select a portfolio of projects that better balance the three dimensions.

Scale and depth do not necessarily have to be in conflict. In some business models, scale might even facilitate superior quality or lower cost of service – as with eye surgery at Aravind Eye Care or heart surgery at Narayana Health in India. Even in such cases, however, trade-offs often lurk beneath the surface. For example, despite its services already being priced quite low, Aravind has to offer further subsidies to achieve its goal of not turning away even the poorest patients.

In an earlier INSEAD Knowledge post on a “spectrum” of business approaches, I described how social enterprises differentiate themselves from more mainstream businesses by pursuing superior depth (making a bigger difference in the lives of the target population), and from charities by striving for longer duration (stretching each dollar of investment through a self-sustaining business model).

Even as mainstream companies now seek purpose and engage on environmental, social or governance (ESG) issues, social enterprises operate on the frontier as society’s R&D outfits, experimenting with cutting-edge business models. The hope is that many of the new models would ultimately be ready to be broadly adopted and scaled in a way that simultaneously delivers meaningful depth of impact as well.

-

View Comments

(3) -

Anonymous User

At the end, any organization should have a mind and a heart for a balanced, healthy and long-term vision. Let us give the heart component an equal space.

This is not about donations, well-intended CSR activities, another long-term investment case with uncertain results or isolated access programs, it is about a disruptive, long term sustainable business model with social measurable outcomes; a business transformation with a real purpose.

Thanks a lot for sharing.Anonymous User

A great piece that gives excellent insight into the aspects of impact that are so crucial to consider and are so often ignored or forgotten. Measuring that 'depth' is key and needs careful planning and thought. The scale element is also often a fascinating aspect because an intervention oftentimes affects not only their direct stakeholders but indirectly creates value/impact for other groups. Thanks Jasjit for your article.

-

Leave a Comment

Anonymous User

07/01/2021, 11.57 pm

Jasjit, great contribution, many thanks for sharing. Let me specifically share my thoughts on scale and measuring. The # of famers example is excellent, as one should indeed go beyond ouputs and zoom in on outcomes and impact. For example, have the reached farmers gained knowledge, does the knowledge stick, does the knowledge gain (measured against a baseline) lead to behaviour change and most importantly, could this lead to (desired) impacts of a district or country? This rigorous process requires time, brains and money upfront to think through.

Given the need for a higher number of public private partnerships and also increased substance in these partnerships, attention needs to be spend on outcomes to avoid only the low hanging fruits are being picked and reported.