Most remote working prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was either a perk for a lucky few, or a peculiarity – something that call centres and a few tech start-ups could offer to all their employees. Data from these outliers ran the risk of being irrelevant to most sectors of the economy. The COVID-19 pandemic has effectively forced a regime change, where people in all sectors have had to work from home, and our survey launched three weeks ago was an attempt to get a first look at how they are coping.

We received 429 responses from 58 countries (maximum representation from the Eurozone, India, the United States, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and Australia), spanning a range of industries and company sizes (50 percent have at least 1000 employees). The respondents varied in the hierarchical levels they occupied, and were almost all knowledge workers who made decisions, managed people, provided services and produced intangibles.

Altogether, our findings contain good news and bad news about the ongoing transition to remote working. While the technological side of the adaptation seems to be proceeding more smoothly than may have been expected, the organisational side is presenting serious challenges. The sooner managers begin to address these challenges (see our recommendations below), the better it will be for individuals and firms.

First, a caveat: the responses to our survey are most representative of the INSEAD/LinkedIn ecology and not the workforce at large. Also, since we rely on respondents for data on both outcome and predictor variables, we are capturing the relationships as they conceive of them, not necessarily those that exist. We should treat our results as a window on how knowledge workers in this ecology (where academics, management consultancy and tech is over-represented) see themselves adjusting to remote working.

1. On average, 40 percent of our respondents indicate improvement in their productivity when working remotely from home. 37 percent say there is no difference, and the rest (23 percent) note a decline in productivity.

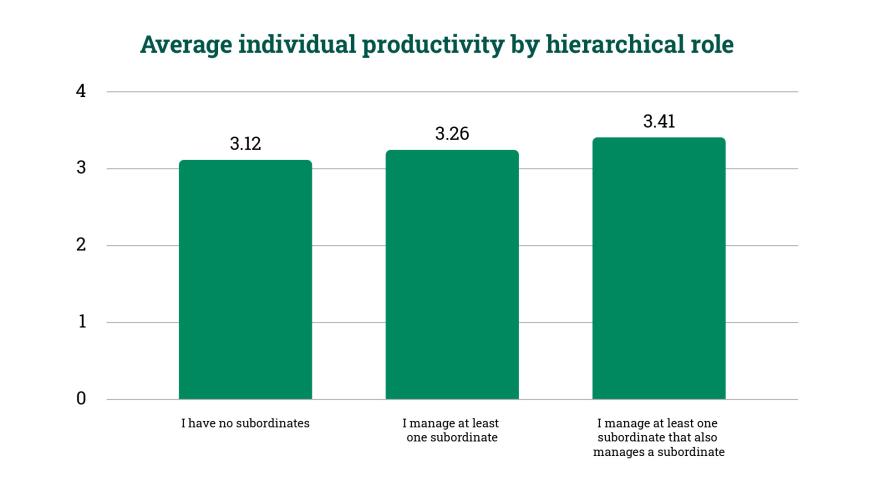

2. Whether their self-reported productivity improved or worsened did not vary much by the size of their company or the industry it was in, or even by the nature of their work – whether it primarily involved managing people, making decisions etc. The age of the respondents did not matter either. Rather, seniority (i.e. respondents who managed subordinates who themselves had subordinates) and prior experience with remote working before the COVID-19 shock were associated with productivity improvements from remote working. This is good and bad news: even in industries where physical interaction for frontline workers are unavoidable, the work that middle and senior managers do may be perfectly feasible to do remotely. Further, people get better at it with experience. This suggests that when we ask “where can remote working work?”, the answer should not be in terms of industry, but hierarchical level. The bad news is that to the extent remote working is seen as a benefit (more on this below), it increases inequality across hierarchical layers.

3. There were significant differences across countries in self-reported productivity due to remote working. It is possible this corresponds to variations in government policies on schools closing and social distancing which were staggered across the sample. It could also just be cultural differences in how people respond to surveys.

4. In this sample, 80 percent of the respondents agreed that their technology infrastructure was effective at supporting their remote work, but only about 50 percent agreed that their manager was supporting their remote working effectively and 63 percent agreed that their organisation laid out clear procedures and processes that were supportive of effective remote work.

At least in this slice of the workforce, the key bottlenecks to transitioning to remote working may be organisational, not technological. On the positive side, only about a third worried about how they would be evaluated by their managers when working remotely. That’s not so surprising since everybody, including the manager, is now working remotely in most instances.

5. The strongest self-reported positive correlates of productivity are improved work/life balance due to remote working, avoiding commuting and prior experience with remote working. Again, a concern with inequality arises here: Improved work/life balance is most likely to be reported by those who can avoid commuting and have effective workspace at home.

6. The strongest self-reported negative correlates of productivity are the missing social interaction with colleagues and distractions at home. Interestingly, the lack of social interactions with colleagues is as negatively associated with productivity for those whose work needs them to be in constant communication with their colleagues as well as those for whom it does not; as organisational scientists have long known, social interactions at work serve a motivational purpose beyond coordinating work.

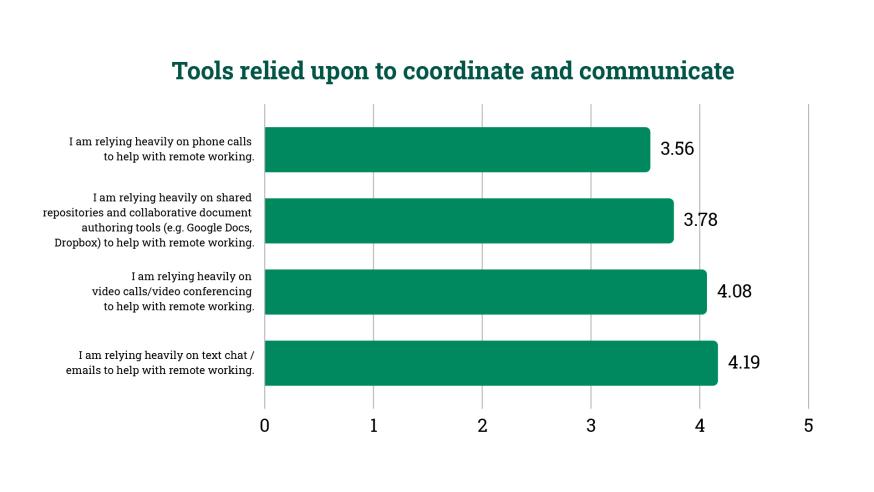

7. Communication tools: The tools used (in order of importance, most to least) are text chat/email, video, repositories/co-authoring tools and phone (with senior managers being more likely to use the phone). People in jobs requiring constant communication use these tools more and also engage in more group communication (instead of dyadic communication) as a response to group working. The data reveal a myopic tendency we have also seen in previous research: When coordinating remote work, the tendency is to default to synchronous communication tools (like video and chat). However, restructuring work procedures (to reduce the need for constant coordination) and relying on asynchronous tools (like repositories/file sharing) is less utilised. This should be a concern for two reasons:

a) Real-time digital communication tools are still an inferior substitute for co-located interactions to coordinate interdependent work; if possible, remote work could be restructured to be made independent instead.

b) Asynchronous tools are more flexible, allowing colleagues to collaborate without being available to communicate at the same moment. The need to make the move quite suddenly to remote working may have left little time to consider these opportunities, but as we settle into an extended period of working like this, organisations might need to revisit these choices.

Managerial recommendations

How can managers intervene to ease the organisational transition to remote working? We have a few ideas, for starters:

- While video conferencing is valuable, particularly for discussions that require rapid iteration, restructuring work processes to make work more self-contained if possible or allowing for asynchronous coordination (e.g. shared documents/files) are alternatives worth considering. Both are standard techniques to aid remote collaboration in software development, which we have studied for several years now, and they can help ease the burden not only of different time zones but also on workers struggling to balance childcare and other domestic responsibilities at home with work. Bear in mind, your employees may not have access to effective work space and freedom from distractions at home.

- Social isolation is a concern and should be combated: Push for some online socialising even if it feels unnatural initially. Occasional video calls with no specific agenda and online gaming are two options to consider. At the same time, it is important to respect boundaries: work without an office does not translate to unlimited working hours. There must be clear “off” times when employees should not feel obligated to respond to chat/mail/calls.

- Managers can see the current crisis as an opportunity to improve their written communication skills – concise, unambiguous writing is critical for remote collaboration – and virtual team management skills. Remote work may have arrived suddenly for most companies, but it will not disappear as quickly, even after the pandemic subsides.

- Use the data that forced working from home is generating to really understand how your organisation works. There was the formal org chart, but now you have the X-ray of real interaction patterns of the organisation in the Zoom/Slack/Teams logs. Perhaps you can rethink how your organisation design can be improved using this data (reach out to us if you need help).

We’ve decided to leave the survey up and publish regular updates as new data accumulates. We’ll be back with more analysis based on the descriptive text from our survey soon. Also, some of our fantastic MBA students have joined us to help create a diagnostic tool based on the survey for companies to benchmark how well they are transitioning to remote working compared to our sample.

Anonymous User

20/07/2020, 07.55 pm

Hi Friends, I love the early focus on data for informing how remote workers are coping during COVID. Also the insight that at this point the bottlenecks really aren't technology but organizational; I think that matches what we've seen in the last few months as folks adapt. I noticed you didn't specific mention team building with remote teams. If you update in the future, I have some suggestions that may help. For example, teams definitely need social connections / bonding time that they are missing out on by not being in the office. Virtual team building activities (quick, easy, free) can help a lot.